Hungry Azure WebJob - Journey of Memory Analysis

Background

We do have some of the stuff push out to the cloud infrastructure. One of the component is WebJob that runs 24/7 and is set to trigger every 2 seconds. You might be wondering why we are not modern and not running stuff in serverless world (for example Azure Functions)? We do have that stuff also, but here take is that we need access to previous run results (there are some heavy caching requirements) and latency that we would need to pay to get access to persistent storage is too much for us.

So running something 24/7 for every 2 seconds sounds like service which is checking patient heartbeat and reacting on any deviations. It’s almost true, but in our case patients are public transportation passengers.

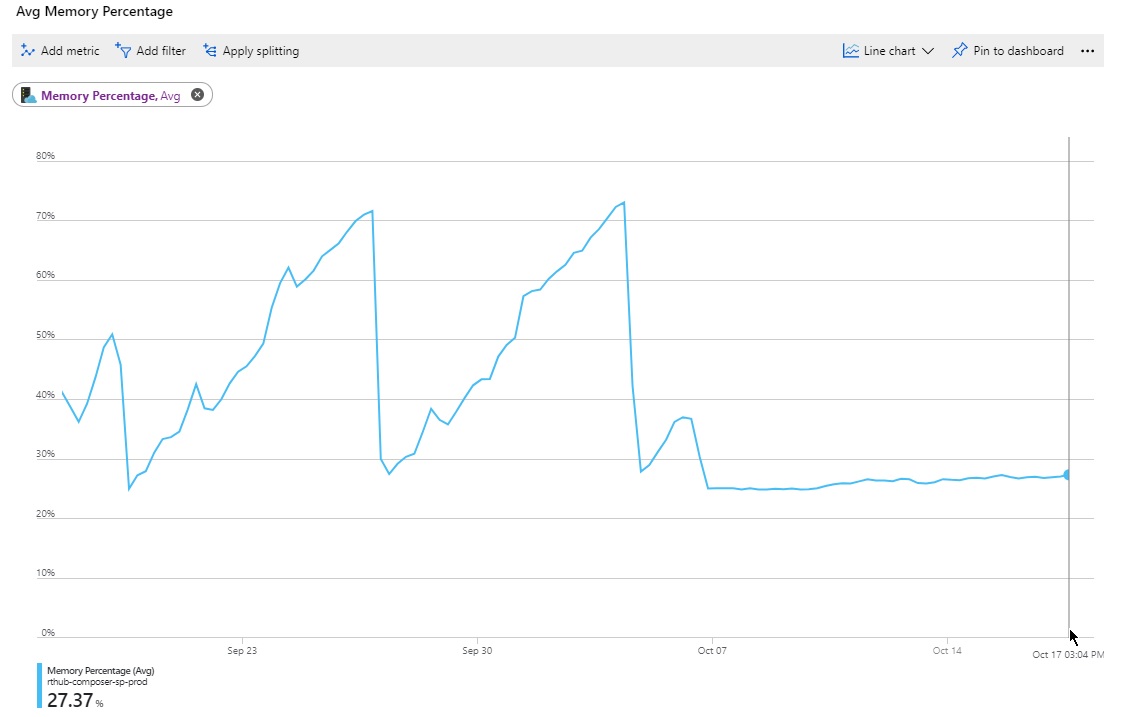

So at some point, I received complaint from customer that our service is “stopped” and nothing really happens and then after some time it’s back to the normal. For me this sounds like peak of something and it’s reset. As there is no end-users connected to the service, there can’t be any peaks because of high traffic. It should be more or less constant workload.

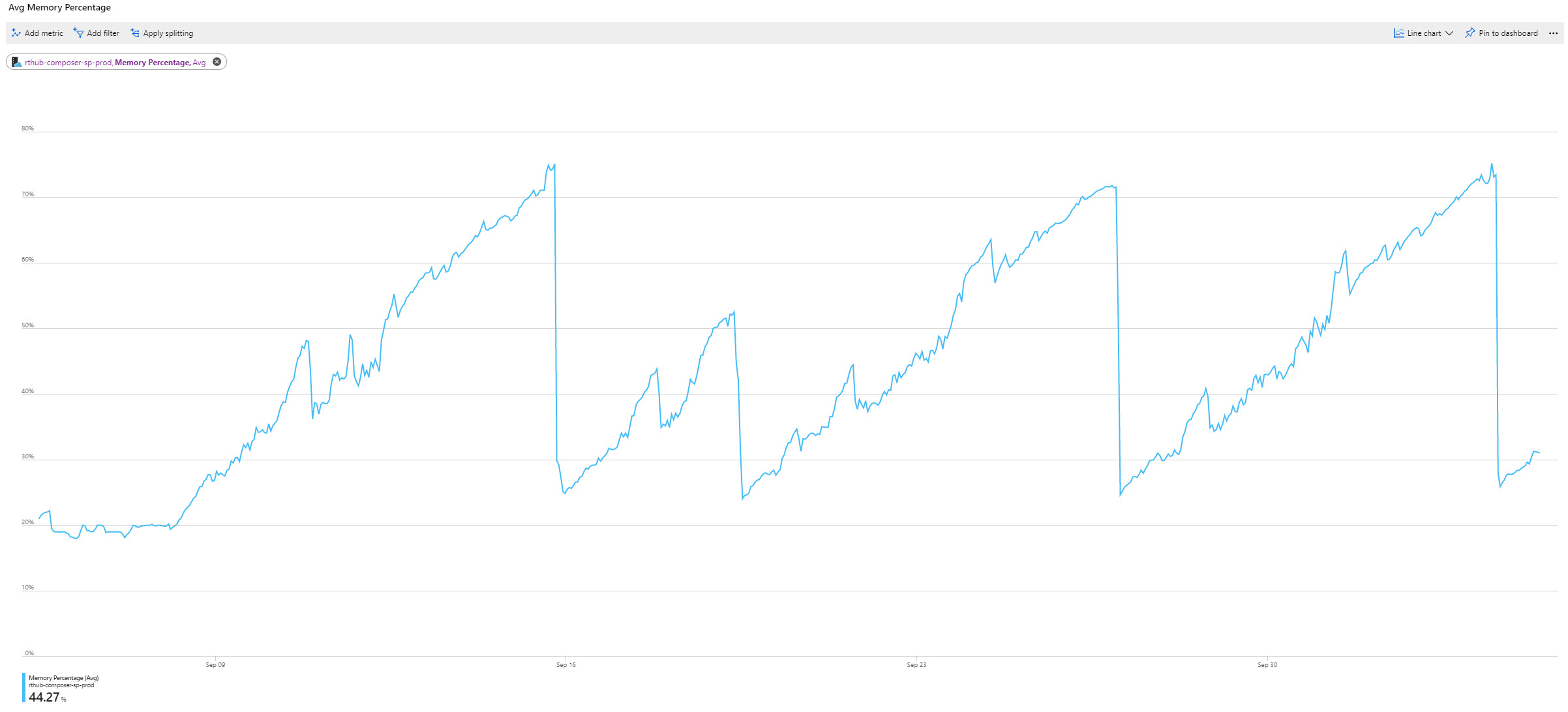

Then I took a look at Service Plan resource utilization.

Dump Analysis

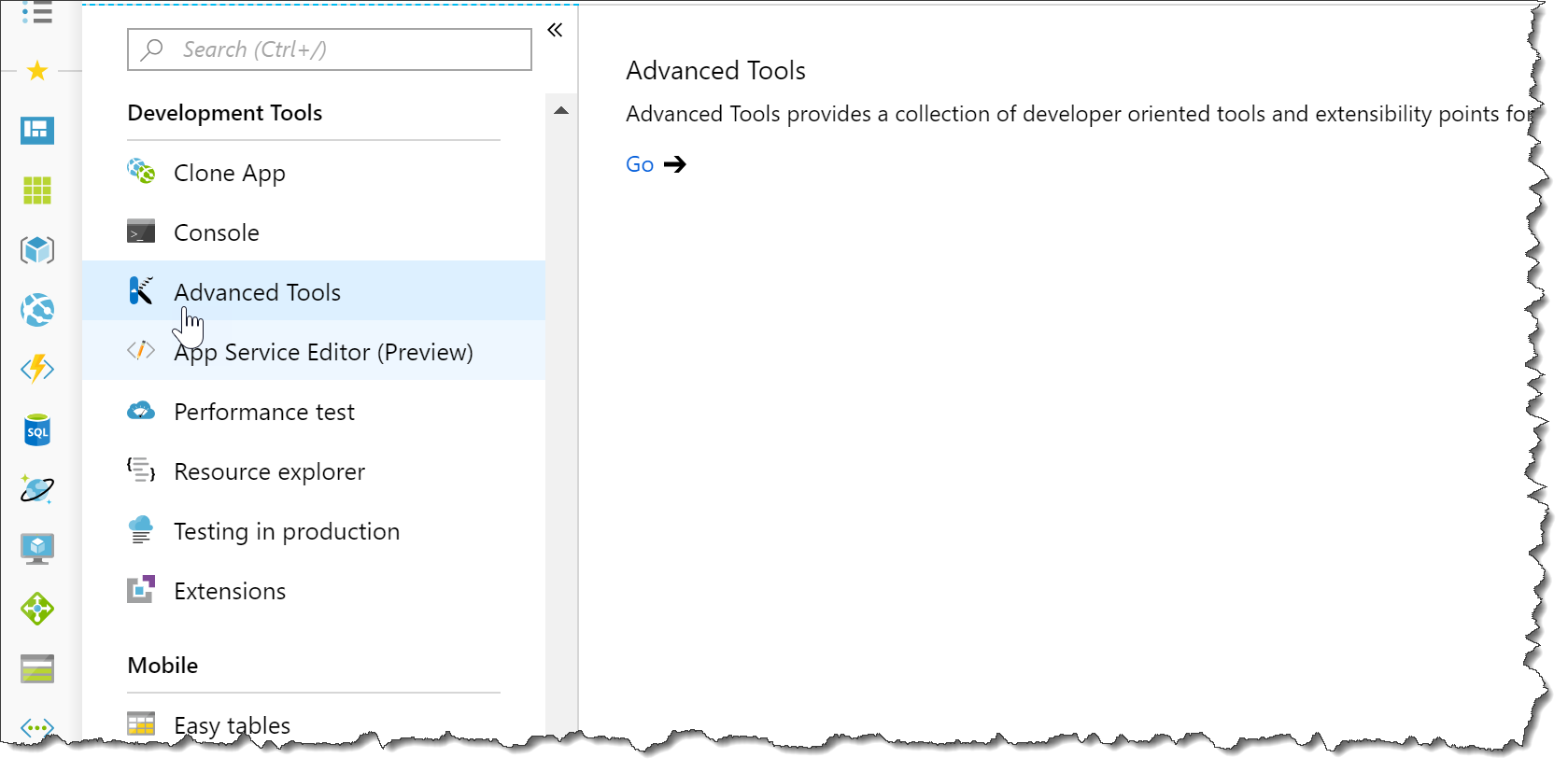

It is actually very convenient to grab a process dump straight from the Advanced Tools (aka Kudos console):

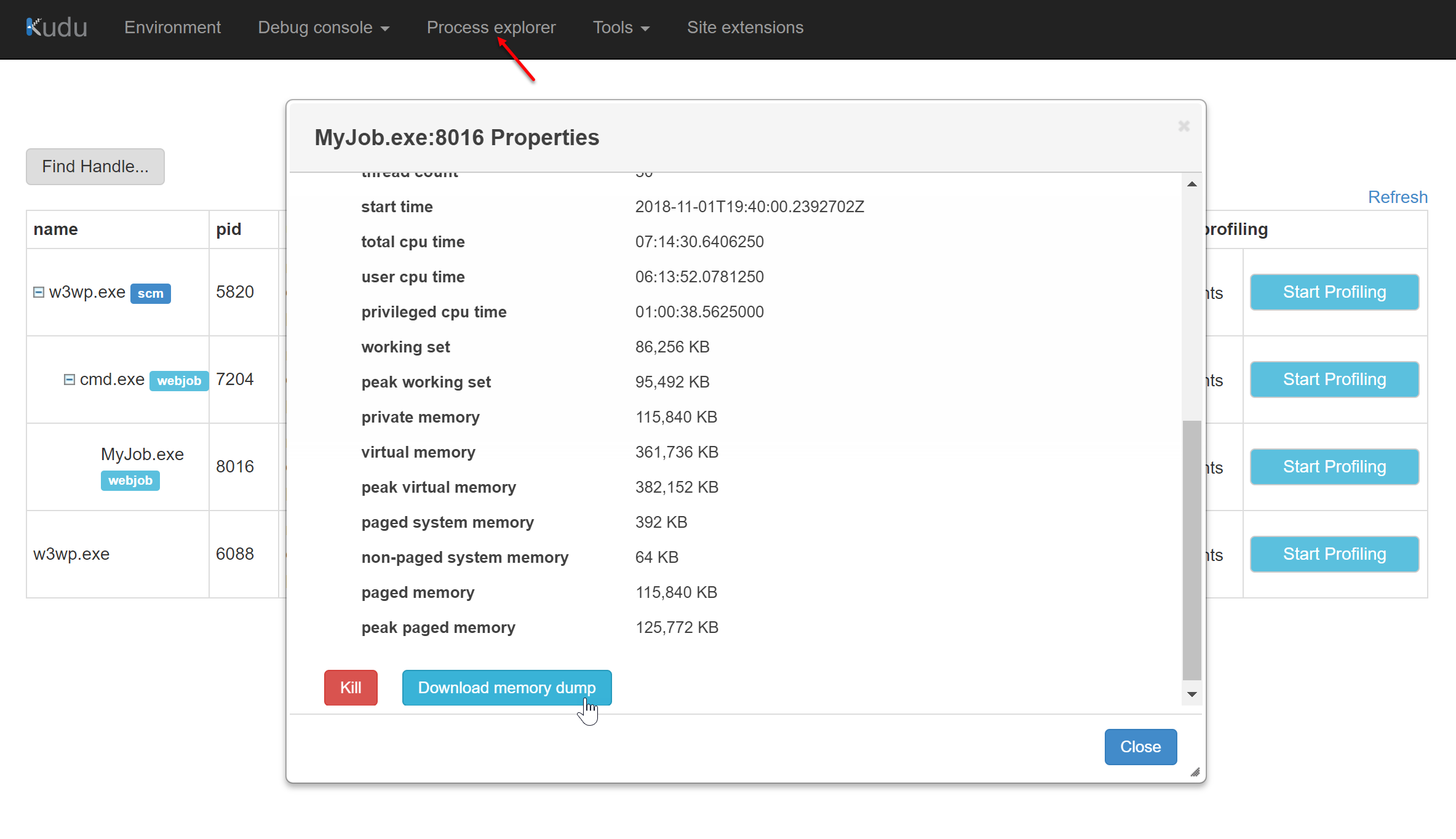

And then dump is available under Process Explorer section:

Now what should I do with this dump?

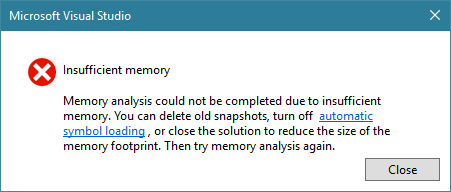

Firstly, I tried couple times to utilize Visual Studio for this, to run some memory analysis there, but it ended up with this error all the time (I’ve read that it’s not related to available memory on your laptop at all, but with the underlying architecture in which VS is running).

What else?? Of course, your best friend - WinDbg to the rescue (to be honest - nowadays I much more prefer WinDbg Preview)!

First we need to let WinDbg to analyze the dump - !analyze command does this.

When win debugger got an idea of what’s going on - we can take a look at managed heap.

> !eeheap -gc

f1010000 f1011000 f1770350 0x75f350(7730000)

f5010000 f5011000 f5631fb8 0x620fb8(6426552)

Large object heap starts at 0x02b21000

segment begin allocated size

02b20000 02b21000 03a31948 0xf10948(15796552)

f6010000 f6011000 f67ad3c0 0x79c3c0(7979968)

b4010000 b4011000 b4cd7c08 0xcc6c08(13397000)

Total Size: Size: 0xdbecfd08 (3689741576) bytes.

------------------------------

GC Heap Size: Size: 0xdbecfd08 (3689741576) bytes.

GC heap size of 3689741576 (around 3.5GB) seems a bit too much for me. It’s definitely a memory leak somewhere. Which gets cleaned up when GC is under pressure and memory consumption threshold has been reached. That’s why we can see some drops of the memory time to time.

Next what we can do is to dump statistics about the heap (note this operation might take a while as it needs to sum up count and size of all types found on the heap).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

> !dumpheap -stat

...

718ad824 8872810 106473720 System.Object

06630b10 3976024 132126336 GeoJSON.Net.Geometry.IPosition[]

71911e28 9787140 234891360 System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary`2+Node[[System.Type, mscorlib],[System.Boolean, mscorlib]]

718ad484 5299303 452138906 System.String

05e9feb8 21103512 844140480 GeoJSON.Net.Geometry.Position

Total 124613918 objects

Among the others high volume objects there are couple interesting cases:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

...

01036f40 305849 11010564 StructureMap.Container

0103c794 305895 11012220 StructureMap.Graph.PluginFamily

...

0164b9b4 305895 18353700 System.Collections.Generic.Dictionary`2+Entry[[System.String, mscorlib],[StructureMap.Pipeline.Instance, StructureMap]][]

0402e37c 305849 19574336 StructureMap.Pipeline.ObjectInstance

0103c494 305850 19574400 StructureMap.Graph.PluginGraph

...

06630348 305849 23244460 GeoJSON.Net.Geometry.Polygon[]

01643e28 611698 24467920 System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary`2[[System.Int32, mscorlib],[StructureMap.Pipeline.LazyLifecycleObject`1[[System.Object, mscorlib]], StructureMap]]

...

04112344 3670178 44042136 StructureMap.Pipeline.LazyLifecycleObject`1+Boxed[[System.Object, mscorlib]]

...

06630494 3976025 63616396 GeoJSON.Net.Geometry.LineString[]

01643dc0 3670178 73403560 StructureMap.Pipeline.LazyLifecycleObject`1[[System.Object, mscorlib]]

This definitely shows up as weird and needs more investigation. If there is a huge number of StructureMap’s Container instances, this means that somewhere in the code there is a creation of the container and not proper disposal.

We can dump all the instances of the Container object:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

> !dumpheap -type StructureMap.Container

Address MT Size

...

02879a7c 0402dc98 24

02879e48 05279c4c 20

...

16a4d688 01640d60 36

...

There a lot of instances of this type. So I even did wait for the WinDbg to finish enlisting (just killed it). But it’s a matter of getting details about single instance of the Container (let’s pick random one).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

> !DumpObj /d 16a4d688

Name: StructureMap.Container

MethodTable: 01036f40

EEClass: 012192fc

Size: 36(0x24) bytes

File: D:\local\Temp\jobs\continuous\WebJob\klbujtvv.m45\StructureMap.dll

Fields:

MT Field Offset Type VT Attr Value Name

01640d60 400000f 4 ...r, StructureMap]] 0 instance 16a8cdec _children

0103b73c 4000010 8 ...ap.IPipelineGraph 0 instance 16a8cc6c _pipelineGraph

718ad824 4000011 c System.Object 0 instance 16a8ce38 _syncLock

718f1f0c 4000012 1c System.Boolean 1 instance 0 _disposedLatch

01036dd8 4000013 14 System.Int32 1 instance 1 _role

718ad484 4000014 10 System.String 0 instance 16a8ce44 <Name>k__BackingField

01036e8c 4000015 18 System.Int32 1 instance 1 <DisposalLock>k__BackingField

Next thing to query dump file is to understand who is keeping (at least this instance) alive. This is achieved with gcroot command.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

> !gcroot 16a4d688

Thread 29fc:

00d9ef18 040ecf9a Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.JobHost.RunAndBlock()

edi:

-> 01b7483c Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.JobHost

-> 01b748e4 Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Host.Executors.JobHostContextFactory

-> 01b73a84 Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Host.Executors.DefaultStorageAccountProvider

-> 01b737ec Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.JobHostConfiguration

-> 01b73954 System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary`2[[System.Type, mscorlib],[System.Object, mscorlib]]

-> 01b73a6c System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary`2+Tables[[System.Type, mscorlib],[System.Object, mscorlib]]

-> 01b739e4 System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary`2+Node[[System.Type, mscorlib],[System.Object, mscorlib]][]

-> 01b74568 System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary`2+Node[[System.Type, mscorlib],[System.Object, mscorlib]]

-> 01b74670 MyProject.WebJob.StructureMapActivator

-> 01b220e4 StructureMap.Container

-> 01b375e4 System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentBag`1[[StructureMap.Container, StructureMap]]

...

What caught my eyes is this line:

1

01b74670 MyProject.WebJob.StructureMapActivator

Which means that there is a “not runtime” class instance that keeps reference to the container. Let’s take a closer look.

WebJob Source

Let’s look at WebJob source code. This is basically the essence of the job (all not relevant details are removed).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

public class Job

{

private readonly IService _service;

public Job(IService service)

{

_service = service ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(service));

}

public async Task RunJob([TimerTrigger(typeof(JobTrigger))] TimerInfo timerInfo)

{

await _service.RunAsync();

}

}

Essentially most of the time our idea about webjobs or functions is that those are just a hosting infrastructure part of the system. They are responsible to let the component from the domain to be run in particular environment. Web job or function is just a shell layer infrastructure code in overall architecture (e.g. pizza architecture)

There is not a big deal to understand what webjob does. But how it gets injected IService instance in construction? This leads us to right direction of our analysis.

Dependency Injection In WebJobs

Once I blogged about how to implement your own dependency injection. I could of course go with Pure DI. But we decided to utilize StructureMap in our WebJob area as well (because we are using it everywhere else and team is used to that).

I’ll not repeat whole blog post about dependency injection here, but just extract relevant parts.In order to support injections in webjobs, runtime actually already supports this with extension point - called job activator.

This is configured in your Main() method:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

static void Main()

{

var container = ComposeContainer();

var config = new JobHostConfiguration

{

JobActivator = new StructureMapActivator(container)

};

if(JobConfig.IsDevelopment)

config.UseDevelopmentSettings();

config.UseTimers();

var host = new JobHost(config);

host.RunAndBlock();

}

In code fragment above ComposeContainer() is just a method that configures and returns Container instance for the job activator to use. Let’s look at StructureMapActivator code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

public class StructureMapActivator : IJobActivator

{

private readonly Container _container;

public StructureMapActivator(Container container)

{

_container = container ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(container));

}

public T CreateInstance<T>()

{

var nestedContainer = _container.CreateChildContainer();

var function = nestedContainer.GetInstance<T>();

var disposableFunction = function as BaseFunction;

disposableFunction?.SetChildContainer(nestedContainer);

return function;

}

}

Activator main responsibility is to create child container for every job execution.

NB! Reviewing stacktrace and also long-lived instances of container lead me to the conclusion that job activator had to create nested containers instead (and not child containers). Nested containers would behave very similar to as it would work in web request context - for example in ASP.NET application. I’m glad that we had this issue - this helped to fix container type usage as well!

Back to track about job activator. Every single dependency resolver (or composition root) purpose is to resolve dependencies. But most importantly it’s also responsible for releasing resolved dependencies. This is just a good behavior of triple R (RRR pattern).

As you can see IJobActivator definition has just a single method - CreateInstance. Disposal pattern is implemented in the runtime. Runtime tries to dispose resolved job instance when it’s done its work (fragment from Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Host.Executors.FunctionInvoker<TReflected>):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public async Task InvokeAsync(object[] arguments)

{

await Task.Yield();

TReflected instance = this._instanceFactory.Create();

using ((object) instance as IDisposable)

await this._methodInvoker.InvokeAsync(instance, arguments);

}

This means that if returned job implements IDisposable then runtime will dispose it. Otherwise - nothing will happen. Interestingly to note that null is also supported as valid using argument.

The only way how StructureMapActivator could implement disposable pattern is to push this responsibility to the job itself. Because once job instance is resolved activator walks off the stage. It’s not involved in further lifecycle management process of the job.

What happens when job is activated?

1

2

var disposableFunction = function as BaseFunction;

disposableFunction?.SetChildContainer(nestedContainer);

Nested container is passed down to job instance. Why? Just because someone needs to dispose it. And unfortunately it’s particular job’s responsibility now.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

public class BaseFunction : IDisposable

{

private IContainer _childContainer;

public void Dispose()

{

_childContainer?.Dispose();

}

public void SetChildContainer(IContainer nestedContainer)

{

_childContainer = nestedContainer;

}

}

Root Cause

Just for a second, let’s glimpse on the definition of our job:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

public class Job

{

public Job(IService service)

{

...

}

public async Task RunJob([TimerTrigger(typeof(JobTrigger))] TimerInfo timerInfo)

{

...

}

}

Yeah!

1

public class Job { ... }

So where is BaseFunction? You know..!? Just forgot to put it there.. Genius!

This is the simplest resolution I’ve ever have done..

1

public class Job : BaseFunction { ... }

Now, every time job finishes its work - nested container is properly disposed.Memory consumption now looks much nicer:

Happy diagnosing!

[eof]

Comments powered by Disqus.